The thorn in my semester November 26, 2013

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, teaching.Tags: failure, grades, students, teaching

1 comment so far

There are two things I hate about being a teacher. The first is dealing with angry, threatening students. Fortunately, I don’t run into those too often, but they are seriously unfun. The second is dealing with students who don’t show up (sometimes physically, sometimes mentally) but still want to pass the class. This problem is more common than the first, though, so I’ve had to learn to get used to it.

The very first semester I was teaching, as an undergrad, I had a student who missed a couple labs. This student in particular annoyed me because it was someone I knew through other activities. When I introduced myself to the class, he said to his neighbor, quite audibly, “She’s the teacher?! This class is going to be SO easy.” The department policy was that anyone who missed more than a certain number of labs would fail, but I tried to be nice and let him make it up. When I set up a time for the first make-up lab, he showed up drunk and could barely function. I complained to the chair, and he got upset with me.

“Why are you letting him make up the labs? This is exactly why we have this policy in place. Fail him.”

I was surprised how easy a decision it was for the chair. Appalled, actually. But the student had been a pain all semester, so I rationalized that I didn’t owe him anything.

I got a call from him over Christmas break: it was my fault that he wasn’t graduating.

I don’t take lightly to guilt trips, so any residual guilt I had about failing him disappeared in that moment. The maneuver backfired, and I told him to take it up with the chair.

I’ve always wondered if his comment about the class being easy was an indicator that he thought he wouldn’t have to put in any effort. I also realized that he was right: if the chair hadn’t told me to fail him, he likely would have gotten through the class easily. That one was my fault: he accurately predicted that I was going to be much nicer than I had to be, and he was going to take advantage of that. I try very hard not to do that any more.

I really hate every time I have to go through this with a student. It’s not that I put a lot of faith in grades, but I would really rather that the students put in enough effort that I can at least justify passing them, even if just barely. It’s much easier on all of us.

When persistence isn’t a good thing… December 19, 2012

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, engineering, teaching.Tags: cheating, grades, teaching

2 comments

I unfortunately have to turn in some forms describing how I caught some students cheating.

This is frustrating because every semester since I started teaching, I have managed to catch at least one cheater. I keep hoping that I’ll get through a semester without dealing with this issue, but I suspect that the reason I might not catch any cheaters is because they’re getting better at it or I’ve overlooked something. It would be nice, however, if it meant that they’d actually stopped.

I’m very confused why students would cheat in my class. I have a very open policy where I encourage them to talk with each other. I basically tell them I think they’ll learn a lot from each other. My big no-no is doing the copy/paste routine and then submitting it as one’s own work. I am very explicit about this. It seems ridiculous that someone would do this given they can talk to each other and look over each other’s shoulders. Apparently it’s too much temptation, however, and some students can’t seem to stop themselves from taking a final step over the boundary into unethical land.

Am I missing something here? January 27, 2012

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, engineering, science, teaching.Tags: grades, homework, teaching

7 comments

Like everyone else, I came across the article on why college students leave engineering.

I was reading it with my jaw hanging open. Specifically this:

The typical engineering major today spends 18.5 hours per week studying. The typical social sciences major, by contrast, spends about 14.6 hours.

My first thought was: Where the heck can you go to school and study for 18.5 hrs/wk and still manage to pass enough classes to get an engineering degree?!

My second thought was that it explained something that has been puzzling me. Last semester, my students complained about the amount of homework I assigned for my 1-credit class. There was about 1 homework assignment per week, and I figured this meant they’d be spending an average of 1-2 hours outside of class on assignments.

When I started school, the rule of thumb was that 3 hours per week outside of class PER CREDIT was required for an A, two for a B, one for a C. This meant that if you planned to go to school full time (which was 12 credits per semester) and get an A average, you needed to be spending about 36 hours per week just on homework in addition to your 12 hours of seat time in a classroom.

I also learned that, for some classes, this was a significant underestimate (usually math, engineering and physics classes) while for other classes, it was an overestimate. I remember one senior-level sociology class that I took where I spent, on average, three hours per week on homework and still came out with one of the highest grades in the class. This is why I always felt it was a good idea to have a nice balance between technical and non-technical classes: it would even out the homework load a bit.

My understanding of a typical homework load is obviously a couple decades behind. (Although I am not sure I plan to change my tune any time soon.) However, I did feel good about one point in the article:

STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) have also had less grade inflation than the humanities and social sciences have in the last several decades.

Apparently you can study less in engineering than you used to have to obtain a degree, which I have to admit bothers me a bit. However, it’s still harder than humanities and you’re more likely to actually have to earn those grades. Despite the fact that we’re probably pushing STEM fields more than we really need to, I do hope employers take that into consideration. STEM students have to be more committed to make it through their fields, which are also more technically challenging. I’d think that should be worth something.

Lessons learned: teachers need organizational skills, too December 19, 2011

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, teaching.Tags: classes, grades, grading, homework, teaching

3 comments

I have now developed a greater understanding of a strange professorial quirk that I observed over the years. I had at least one professor each term who would get visibly annoyed if you tried to give them an assignment at any time other than the first thirty seconds of a class period.

My understanding is due to that fact that I have recently become eligible to join the Super Secret Society of Teachers Who Have Lost a Student’s Assignment. (I’m suffering from a cold, so I was unable to come up with a snappy acronym. Please feel free to make an effort on my behalf.)

*headdesk*

When I was teaching geology labs, I was usually teaching four sections each week in a different building. I found that the best way to keep track of student work was to have four plastic filing envelopes. Each envelope was a different color, and I always knew which one to grab before each class. At the beginning of class, I’d hand stuff back. At the end of class, it would all get filed away in my envelope. This was straight-forward, and I never lost any homeworks this way. The labs were done in class and handed in at the end. If they had to hand something else in, it went into my mailbox, which was in the same building as my office (but different than the labs).

This semester, I had 90 students in four classes, in three buildings. My mailbox was in a different building than two of my classes, and all of them were in different places than my regular office. I usually had two of my envelopes with me (two classes were on Tuesday and two were on Thursday). Students also had the option of submitting homeworks online, as much as I hate grading those.

What I hadn’t anticipated was running into students who would randomly hand me homeworks between classes, leave them at the department with the admin staff, or all sorts of other unexpected things. And, as it happens, I ended up misplacing some homework. In fact, I went through and filed everything on my desk, and still never found it. I believe it has ended up in the same place that unmatched socks end up…except that paper always ends up falling back out and will likely be found in the spring of 2013 or some similarly odd time.

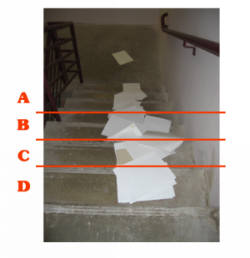

If I end up teaching this class again, I think I’m going to make it a policy that homeworks be handed in online. Sadly, this means that I can’t use the stair distribution when grading:

(Thanks to Concurring Opinions for the image.)

I hate grading in front of a computer screen, but I have to admit that it significantly reduces the organizational demands required to keep track of all the assignments. Lurking in the back of my mind, however, is the idea of having to teach a very large class where homeworks simply must be dealt with the old fashioned way. (And no, I’m not talking about burning them.)

Grading contracts August 18, 2011

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, teaching.Tags: grades, grading contracts, teaching

add a comment

Yesterday, I made a comment on Twitter about using a grading contract for the class I’m teaching this semester. I talked about the specifics of the class in this post at EngineerBlogs. After posting the comment, @profgears and @27andaphd asked me explain a bit more. I’d been planning on writing a post about them after talking about how people impute certain characteristics into grades that really aren’t there. I guess now is as good a time as any.

Contract grading is basically using an agreement between yourself and the student for what grade they will earn in the course. Typically, this contract allows for some choice on the student’s part, and may even include some input, as well.

Essentially, developing a grading contract means you need to consider a few things:

- What assignments are essential to meet the goals of the class? Which assignments are optional, if any?

- What is the minimum level of performance for these assignments and for the class overall?

- How much latitude can you give the student in determining how they will fulfill the requirements?

- How do these requirements fit into a grading scheme?

As an example, I will probably have several assignments which are mandatory and some that are not. I plan to grade these assignments on a binary scale: Pass or Redo. If the student wants, they can revise the Redo the assignments as many times as they want until it becomes a Pass. Most assignments will require a written submission, but there will be the option of completing the assignment through alternate means if the students want to propose something. Final grading for the course will require that they pass all of the mandatory assignments and, depending on what grade they contract for, a specified number of optional assignments. If they fail to meet the requirements of the contracted grade, I will assign them the grade which matches what they actually achieved.

The reason I like this system is because it doesn’t place a lot of undue pressure on the student. I remember that, as an undergrad, I came to the realization that I didn’t have to do all of my assignments perfectly: to get an A, I just needed to do better than everyone else. That was slightly helpful, except that doing better than everyone else always left me with an uncertain and often moving target (depending on the other students in the class)…which was almost as stressful as striving to get perfect grades. The student who uses a grading contract can determine what level of effort they need to get the desired grade for a course. Not everyone cares about getting As, and looking at the requirements at the beginning will get them thinking about where their priorities are within the class and within the whole system of going through school.

Using a grading contract means that grade assignments aren’t relative to people in the class. It’s an absolute measurement, and makes it very clear what is expected of the student…while also allowing a level of flexibility usually not offered in a classroom.

It also enables prioritizing: if stuck for time, the student doesn’t have to do *every* assignment, and the instructor can get across (hopefully) what they consider to be the most important topics of the class.

And I like that there’s the option for the student to chose what works for them in terms of assignment fulfillment. This aspect works best when presenting results for projects. Do they like to give talks better, or do they prefer writing? What are the essential parts of making the project successful?

Finally, I have to admit that I have a very selfish purpose in doing this: I get tired of students arguing about getting one point here and there because they are under the false impression that the one point, worth .03% of their grade, may potentially make a difference in the long run. I really want them to focus on the right things to get good grades, not minutia.

Once you’ve worked out how you want to deal with the contract, each student can sign an agreement stating what grade they are going to work for. This also gives the instructor an idea of what level of effort they can expect from each student: it gives an explicit statement of how much they hope to take from the class.

There are several places to find information about grading contracts on the web, but this is a good summary of the system.

Grades and what they don’t mean March 25, 2011

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, engineering, physics, teaching.Tags: classroom expectations, grades, grading contract, teaching

4 comments

I tweeted a link yesterday to a paper titled, “Everyone should get an A,” by David MacKay. I found it an interesting read because the author’s discussion is quite compelling.

Unfortunately, I just can’t get in line with this argument. As much as I really do like the idea, I can only assume that MacKay is at a university where all the students really are exceptional. I hate to say it, but I have seen people enter a field of interest where they literally were simply incapable of doing the work or had no scruples about cheating on nearly every assignment.

GEARS already responded that he disagrees with this, too, although I think we differ on the reasons why. He mentions the dreaded life or death situation. I personally think this is a fallacy: school of any type is not adequate training when dealing with life or death situations. People who are likely to be put in that situation are usually people who go into the military, fire-fighting, police work, etc. The kind of training they do for real life-and-death situations is significantly different than an exam in school, and exams are completely inadequate indicators of this.

Further, there’s the issue that the kind of skills you need in a life-and-death situation aren’t always the kinds of things you need in school. Every time someone brings this particular argument up, I always think of the above clip from Apollo 13. Admittedly, a good part of the movie involves problem solving by engineers that include things they did in school. However, if you look at the astronauts, they learned their skills through repetition of procedure. And some of the things the engineers were doing probably had very little to do with what they learned in school and involved some raw-problem solving skills, such as the filter issue. I don’t buy the argument that regurgitation on exams is indicative of good problem solving skills.

In fact, the book Teaching Engineering discusses some of this. It mentions that students who do well early on in an engineering program are not always the best problem solvers. They are the best at learning and reproducing processes, which is a set of skills fairly low on Bloom’s Taxonomy. However, that behavior may shift: the students who are very good early on in an engineering program may not do as well in higher-level courses because they are not as good at synthesis and analysis. Some B and C students who struggle early on may be doing so because they tend to function at a higher level on Bloom’s taxonomy, while some of the A students will begin to struggle in classes which don’t emphasize pre-learned processes, rote, and memorization. While this was written strictly about engineering, I would say this is likely true in most fields.

Finally, I think that grades detract from the purpose of the classroom: learning. I, just like every other teacher on the planet, have had students come up to me and argue over points here and there. It has nothing to do with whether or not they understood the material or even cared about it: it was because they wanted a particular grade, and the material was secondary. There are a lot of smart people who could do so much if they weren’t worrying about their grades all the time.

This, to me, means that grades are not always indicative of the ‘best’ students. A grade indicates that a student has the skills a particular person wants in the class they’re teaching. Different classes utilize different skills, however, so I don’t know that grades are really reflective of much except that they met the expectations of a particular class. Without knowing much about the class, you don’t really have any idea of what skills were actually useful. And, of course, the whole time, they’re detracting from interest in the material.

I’ve now established that I don’t agree with the concept of giving everyone As but that I also don’t put much stock in grades. So what do you do?!

I guess that I’ve become a fan of the grading contract. For those who have never heard of this (and I personally have only encountered it in one class my entire career), it is a contract to receive a particular grade. Generally, there are different requirements for each grade. Some professors do this as a flexible agreement with a lot of input from the student while others establish what is required for a particular grade. In reality, this is very much like business: if you have the work done by a particular date, you get paid so much. If your deadline slips, then it is a lesser amount.

I won’t go into the details of how it works much beyond that (maybe in a later post), but I like the philosophy. The student has clear expectations set out at the beginning of the class. They know what is required to get a particular grade. They can choose if they feel it’s worth the effort to achieve such a grade or if they’re happier with something else. Either way, the student is now free to worry about the topic matter and material presented in the course rather than the grade they want to receive and how everything fits into the oft unstated or even shifting criteria.

In turn, the professor isn’t responsible for micromanaging the student’s time. She knows what she can reasonably expect from students. She also has justification for assigning a particular grade, both if the student abides by the contract and if he doesn’t.

This is a more realistic scenario: the student met the expectations given in class, and the grade is merely a reflection of that reality. The classroom can then return to a place where ideas are the primary concern.

I also blog at Engineer Blogs, home away from home to some of the best engineering blogs.

I also blog at Engineer Blogs, home away from home to some of the best engineering blogs.

A clause for pause November 9, 2012

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, societal commentary, teaching.Tags: behavior, grades, rules, students, syllabus

add a comment

I got into a discussion with a colleague where I mentioned that, when necessary, a student’s behavior will be a consideration when it comes time to assign final grades. This colleague said I couldn’t do that because the grade should be based solely on their coursework.

What this colleague doesn’t understand is that almost every semester, I have had one or two students who felt that they were ‘in charge’ and could tell me what I could and could not do in the class. The most egregious examples were students showing up drunk, who felt like they could start yelling at me, or felt like they were entitled to argue with me endlessly once I had made a decision on something. Every. Semester.

A couple years ago, I began adding a ‘behavioral expectations’ to my syllabus, stating that students needed to treat other students and the instructor respectfully. I also outlined behaviors that students frequently have questions about. (No, I don’t mind if you eat or drink during class. You don’t need to ask me to go to the bathroom. If you come in late, don’t disrupt the class, etc.) I needed students to realize there were basic expectations, and more importantly, that I am not a pushover.

This isn’t me attempting to micromanage their behavior. The idea was to get across that I could tell them they were done with my class if they started being very oppositional, disruptive, or even threatening. I got very tired of students who felt it was acceptable to badger me until they got the grade they wanted. All of these scenarios have occurred at one time or another, and I, for a long time, felt powerless to do anything about it.

What I find questionable is giving a student an A, which many people take as a stamp of approval, when the student fought tooth and nail to avoid meeting the minimum qualifications of getting that grade or has created a difficult learning environment for those around them. I’m not a conformist, but I do believe in showing people basic respect. If they cannot do that, then they have not met my requirements to receive a grade that essentially says I strongly approve of how they have performed in my class.