First grade, all over again May 27, 2011

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, gifted, homeschooling, math, younger son.Tags: emotional scaffolding, gifted, gifted education, teaching

add a comment

Some of you know that we ended up switching the younger boy to a new school mid-year. We weren’t sure how the new arrangement would work out, so we also decided to enroll him in EPGY’s math program. I really like program, and one reason is that they introduce basic algebra very early on. He is already comfortable with using variables, and understands some basic concepts, like substitution. He was doing great until a couple days ago. Then we encountered sum and difference equations.

a+b=10

a-b=0

Actually, this particular example was fairly easy for him. You know that if the difference is zero, the values of a and b have to be the same. The problem is when you end up with a difference equation that looks like this:

a-b=4

That seemed to lose him fairly quickly. After struggling with it for a while, I decided it was time to use some manipulatives.

(Note to self: Do not use chocolate chips as manipulatives. If it’s hot, they’ll melt. And regardless of the temperature, the kid will be more interested in eating them than doing math with them.)

I explained that a-b=4 is the same as saying that a has 4 more chocolate chips than b. First we have to take away the extra four chocolate chips, and then a and b will share the remaining chocolate chips equally. So, in this case, they will share six chocolate chips equally, meaning a will end up with 7 and b will have 3.

He seemed to understand. He was able to solve several examples using the chocolate chips, but when we went back to doing the problems on the computer, he seemed lost. He couldn’t do them, and then pretty soon, he wouldn’t do them. I was flummoxed because he obviously understood how to do it a few moments before.

My first reaction was to get frustrated, and soon I was almost angry. He wasn’t even trying!

It was at that point I realized exactly what had been going on at his old school. The kid is a serious perfectionist, and being a perfectionist, his instinct is to avoid things he can’t do very easily. He’s afraid that if he can’t do them easily, he will get them wrong. And getting things wrong is not an option to a perfectionist. (Before you say what a horrible parent I am for turning my child into a perfectionist, please note that he’s been like this since he was capable of doing *anything* and that it’s extremely common in gifted children because they are not used to things being challenging.)

I realized I needed to change my tactics quickly. I immediately told him that I knew it was hard to do these problems, but that if he tried, I was sure he’d do a good job at them. I went from frustrated to empathetic in the drop of the hat. He asked if I would help him if he got stuck, and I promised I would.

And then, suddenly, he could do the problems with no help at all.

In education, this sort of practice is called “emotional scaffolding”: the idea that influencing emotions is as much a part of learning as acquiring knowledge, and for students to learn well, they may need emotional support from their teachers as well as instruction. When I had tried to talk to the teacher at younger boy’s old school about using emotional scaffolding in the classroom, her response was that she was “not a special ed teacher”. I was surprised because, to me, addressing the emotional component of learning is just as important as the content. If you have a kid who is easily intimidated by learning, then it only makes sense they may need more pep talks than the average kid. Making a kid comfortable with learning is most definitely not something confined to special ed teachers – or at least it shouldn’t be.

On the flip side, if you don’t understand the root of the behavior, it is probably very easy to assume that the child doesn’t understand the material. Addressing the emotional component of learning means you need to have a good handle on what makes a child tick – something nearly impossible when you’re dealing with 25 or 30 kids.

I think part of the reason that the younger boy is doing so well in his new classroom is that 1) we have identified the emotional issues causing the problem and 2) he had a teacher who was very willing and able to work with him and provide that emotional scaffolding. As a result, he went from having completely shut down to now working at advanced levels in all of his curriculum.

One issue in dealing with perfectionism, however, is making sure that the child is continually challenged enough to frustrate them a little, but not so much that they are bound to fail. They need to learn that working or getting help is a better way to deal with challenges than simply shutting down. And in order to be willing to confront those challenges, teachers need to be willing to both mentally challenge a child while at the same time providing emotional support.

What I saw the past few days confirmed what I thought had happened – the teacher at the old school was willing to provide the challenge, but not willing to provide any emotional support. The teacher at the new school was able to do both. For that, he will forever have my gratitude.

It is also a reminder to me that teaching material alone is not enough: the best teachers also work to keep their students motivated and interested.

Teaching math without memorization March 2, 2011

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, gifted, homeschooling, math, older son, teaching.Tags: abacus, arithmetic, bead frame, gifted education, homeschooling, math, multiplication, tables

12 comments

If there is one thing I learned in my junior level electromagnetics class that will always stick with me, it’s this:

The permittivity of free space (ε0) is 8.854 * 10 -12 F/m.

And realizing that will always stick with me gave me a lot of insight into what is wrong with the typical approach to teaching math, especially in elementary school.

I know it’s a stretch, but bear with me.

(Totally gratuitous picture of a cute baby bear.)

One of the things I’ve encountered with both my kids is that their teachers are very set on them memorizing math facts. My older boy spent 3rd and 6th grade enrolled full-time in regular public school programs, and his third grade teacher was constantly railing on about how he was ‘bad in math’. In fact, she blamed it on the fact that he’d been homeschooling. (We got this every time we talked to her.) She would go on and on about how he didn’t have his tables memorized. Why, he had to stop and think every time she asked him a basic addition problem!

OMG…thinking in school?! Can’t have that.

I therefore found it very amusing when, prior to the the next school year, his principle pulled out the results of his spring MAPS testing and commented on how good his math scores were because, in her words, “He must know his tables really well.”

By these two comments alone, you can tell what is important to elementary school teachers: memorization of arithmetic tables.

Aside from having a BS in physics, I minored in math in college. Despite the fact that I had enough credits for a major, the credits were in overwhelmingly applied math classes, and there was no applied math major at my school. Suffice it to say that I do have at least a basic knowledge of math.

I also have homeschooled my older child for most of his educational career, and as a freshman in high school, he’s finishing a course in college algebra and trigonometry.

During the older child’s homeschooling years, I never once made an attempt to have him memorize tables of any kind. I did not practice a lot of repetition of basic facts, either. This was because of my experience in my electromagnetics class: I didn’t memorize the value of the permittivity of free space due to repetition and drill; I memorized it because I used it in nearly every problem I did for four months in that class. Yeah, I had to look it up the first dozen times I used it, but after that, it was lodged in my brain. And look…it’s still there a decade later!

I came to the conclusion that if you really need to know something, you’ll learn it through frequent use. But how do you use something that you don’t know?

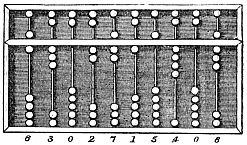

Addition and subtraction are fairly simple: you give a kid a bead frame, abacus, or even a ruler (the original slide rule!) and show them how to perform addition and subtraction operations using beads or moving up and down a number line. Then you can move them quite quickly through addition and subtraction of infinitely (okay…not infinite) finitely large numbers. You can let them go through increasingly complex topics without ever making them memorize a table. In fact, after a short time, you’ll find that they are pointing at beads or rulers in the air, counting out the solution to their problem. And after that, the invisible ruler or beads will be sitting in their head, being manipulated by mental fingers. Finally, they won’t even have to think about it…they’ll just know.

The image on the left is an abacus, while the image on the right is a bead frame. Bead frames are easier to find and manipulate, in my experience.

|

|

Multiplication should be taught as addition of groups of objects, and division as ‘counting’ of the number of groups in the whole. Once kids have mastered the process of multiplication and division, you can then simply print out a multiplication table. I had my older son paste it on the inside cover of a notebook or the front of a folder so that he could always find it. You may find that some kids prefer to go back to the bead frames. (And if you are really lucky, you have an abacus and know how to use it for multiplication…which I don’t.) Any method is fine as long as it works for your child. But the point is that you can then let them progress through more and more complicated arithmetic involving those operations (such as multiplying large numbers or long division) using the table or other device to look up values. Again, as you progress through these concepts, they will slowly begin to memorize them.

As a homeschooler, the curriculum that I chose for math was fairly important as well. I liked Singapore math for it’s focus on simplicity and conceptual explanations. Everyone raves about the ‘mental math’ tricks that are taught in the series. And they’re right: mental math is awesome. However, the only reason the series does it so effectively is because it teaches the concepts in a way that you can then make logical simplifications in process that result in ‘mental math’ and good estimation skills.

(My only complaint is that they don’t teach the lattice method of multiplication. I think the ‘traditional’ method of multiplying large numbers is much better suited for estimation methods, whereas the lattice method is definitely superior for calculating with precision.)

To me, the important part of all of this is to make sure that they understand what the process of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Kids can memorize facts for quick recall, but if that is the emphasis and they can’t recall a fact, they’re going to be stuck. If the emphasis is instead on teaching arithmetic as a process, they can always figure it out should they forget.

And really, arithmetic is a process. I came across an article on Hoagies’ Gifted site called Why Memorize? I have to take big exception to the article because it says that math is a lot of dry facts. If you teach it as memorization of facts instead of a process of manipulating numbers (or objects or motion in space), it sure is! But I can tell you that it’s not, and as you advance to higher level classes in mathematics, reliance on the notion that math is memorization will cause you problems and impede your progression.

Finally, I have to wonder if this is why so many elementary school educators fear math: it’s boring memorization of facts. They are never taught how it’s actually a really cool process. If it were taught properly, preferably with a lot of enthusiasm instead of dread, I wonder if a lot of teachers would lose their ‘math-phobia’. And that would, of course, mean their students might start to like math, too.

The presumed snobbery of gifted education February 2, 2011

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, gifted, homeschooling, older son, societal commentary.Tags: acceleration, gifted, gifted education, homeschooling, snobs

11 comments

I was having a conversation with my older boy the other day (it does still happen…despite the fact that he’s a teenager, I haven’t become dumb as bricks yet), and we were talking about people we know who are what I’d call “gifted education snobs”.

I’m sure you’ve met these people: they’re the ones who talk about how their kids will eventually get into Harvard while they can’t even tie their own shoes at 16. Although, if their kid is like Albert Einstein, it might be forgivable. But seriously, these are the people who are pushing kids who are probably reasonably bright beyond their limits or into doing things that make them depressed and frustrated.

The reason they bug me is not because they have kids who may or may not be intellectually superior to my own. Let’s face it: I’ve run into a lot of people who are smarter and more knowledgeable than myself. It’s not even the attitude that they are superior (although I have to admit that can get annoying, too).

What gets me is the notion that their kids are so bright that everything will come easy to them and they’ll never have to work at anything. Because that’s what it means to be smart, right? This attitude is obviously not working for the kid, and it’s giving everyone else a bad impression of what giftedness is or is not, as well as what the parents of ‘gifted kids’ are like.

This attitude is what hurts the rest of us who are advocating for our gifted kids. I imagine from the outside, it all looks the same to someone who doesn’t anticipate their kid will ever get to be in a gifted program. We all just look like we’re trying to give our kids a special advantage over everyone else.

So let me clarify: that’s not at all what I have been trying to do with my kids. There are some things gifted education should do that has nothing to do with a special advantages:

1) I want my kid to learn to work hard. No matter how smart you are, there will always be things that are challenging in life. There will be some point where you hit a brick wall. It’s best if you learn early on how to manage your time, be responsible, and deal with learning new things (which can sometimes be intimidating). Probably two-thirds of most students can get that out of a regular classroom. For half of the other third (or one sixth), it will be too much – and there is a significant amount of funding and infrastructure in place to help these kids (which they very much deserve). However, the other sixth is left to float, in most cases. They’re smart, and for some reason it’s more acceptable to let these kids coast and fight boredom through school than to give them the same appropriately challenging education that most other kids receive.

My older son is learning that there’s a significant difference in effort between his high school and homeschool courses. At most, he spends about two hours outside of school per week doing his high school work. His homeschool work, where he’s learning everything himself, is a lot harder. He’s even gotten extremely frustrated. But that’s what I wanted: he needs to learn to deal with that frustration (that he can learn things that are hard if he keeps trying or gets some help). I want him to know how to deal with this before he gets to college and flames out because he’s never had to those other skills established and honed.

2) Gifted kids, like all other kids, want to feel secure and have friends. They don’t want to be the constant target of bullies. Again, I think this is because most people may not understand how badly gifted kids can stick out. I got tons of complaints about my older son “talking like a professor” in middle school. I never thought he talked oddly because this is the way we talk to each other at home. But in a group of mixed-ability, this sort of behavior sticks out, and the other kids use it as an excuse to bully and ostracize. There has been a lot of research (some of which is listed here) showing that gifted kids are more likely to be bullied than others, even by teachers, because of their differences. The only place many of these kids feel secure and can make friends are when they are with other kids like themselves, i.e. where they won’t stick out like sore thumbs. This sort of arrangement also tends to make them less likely to become overly confident in their abilities because they go from being smarter than everyone else in a regular classroom to the average person. (The fact that they are in a gifted classroom often doesn’t play into their perceptions; they are more affected by their interactions with the people around them than labels.)

So when I complain about my kid not being able to take advanced coursework, it’s not because I think he’s better than everyone else: it’s because I know he’s being deprived of the opportunity to learn the intangible skills that go with being appropriately challenged. It also deprives him of the chance to feel like a normal kid. Both of those things are very important to how he will function as an adult, and far more important to me than having him look like he’s smarter than other kids.

I also blog at Engineer Blogs, home away from home to some of the best engineering blogs.

I also blog at Engineer Blogs, home away from home to some of the best engineering blogs.

Lexile ranges December 19, 2011

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, gifted, homeschooling, older son, science fiction, societal commentary, teaching, younger son.Tags: books, gifted, gifted education, lexile range, older son, reading, younger son

add a comment

The younger boy’s school sent home a bunch of information on lexile range. I’d never heard of this before, but it’s a way to rate books so that kids are reading at an appropriate level. On the surface, it seems like a good idea: it’s very hard, as a parent, to provide reading material for your kids that’s appropriate. Aside from the basic issues of whether they’ll understand the language and sentence structures of a book, there are the themes and situations: are they too complex or adult-oriented for a child to read?

A lot of this, of course, depends not only on cognitive ability but emotional maturity, as well. I remember how my older boy started reading Harry Potter very early. Sometime in third grade, he read the fifth book. I began to wonder about him reading the fourth and fifth books at such a young age because of the adult themes. We were fortunate, however. Reading books about such emotional and adult themes started giving him words to explain a lot of his thoughts and feelings with minimal emotional fallout.

After receiving these results, I dutifully trucked my troops down to the library (no complaints from said troops) where they had a program to help us find books in the appropriate range. However, I forgot the letter with the lexile range and so had to guess where he was at. The younger boy had already been reading Magic Tree House books, so I figured some of the Dragon Slayer Academy books might be up his alley. We got those and some Bionicle books and headed home. He really seemed to like the Dragon Slayer Academy books and has been reading bits at a time. Language-wise, they seemed perfect, although their length is a bit intimidating for him.

It turned out, I had remembered the incorrect values. The books we picked were near the top of his range. And yet, I was confused. If these were supposed to be too difficult, why was he having no difficulty reading them?

Mike, unbeknownst to me, had also started looking at lexile information on specific books. He was curious where he would’ve been placed when he was in various stages of school. After we returned from the library, he started telling me about this and that he didn’t buy the results. He’d been comparing some of his favorite sci-fi books, and he was puzzled at the results. I threw out some books I read as a kid and made some comparisons. Books that I thought were very difficult showed up as supposedly easier to read than ones I’d zipped through.

We looked up the criteria for determining lexile range:

Both Mike and I read this and shook our heads. We both had different takes on it. I found that one thing that made a book challenging for me was dealing with vocabulary. It’s not clear to me whether or not this is reflected in the “word frequency” measure. (Do they mean word frequency in the book or relative to the English language?) Mike felt he struggled most with books that had very adult themes, something not reflected in the range.

Our take on this is that this is only a very rough guideline, and probably not a good one to use. We both felt that interest in a book or topic was probably going to be a far better predictor of readability than using the lexile range. I suppose that’s what they’re saying about considering other factors.

My concern in this is that some schools go a bit overboard with these things. When the older boy was in fifth grade, he was going to public school part time. I got a couple calls from the school librarian because he wanted to check out books that were designated for 7th-9th graders. I felt this was silly because he’d been reading at above that level already, and probably had come across themes in his reading that were more adult than what was in those books. I told her it alright for him to check the books out, but she seemed to be very opposed to it. I finally gave up and told older son that he should just probably check most of his books out from the public library.

I’m hoping I don’t see something similar happen with the younger son, i.e., that he not be allowed to check books out from the library if they’re outside of his lexile range. On the other hand, I’m glad that they seem to be promoting reading at the upper end of the scale so that kids will stretch their mental muscles a bit as well as that they make the point that within any grade level, you’ll have a wide variety of reading levels. In other words, it seems like they’re trying to get rid of the fantasy that kids all read at the same level and thus require the same reading level. Therefore, while I may disagree with assessments of individual books, I think they’re definitely taking a huge step in the right direction.