I walk the line June 24, 2014

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, gifted, homeschooling, older son.Tags: education, gifted, gifted education, high school, homeschooling, homework, older son, perfectionism

3 comments

I’ve been watching the older son grappling with his courses for the past year. He was taking courses through an independent study organization to finish up some credits he needs to enter college. I didn’t feel comfortable with some of these (especially literature classes), so we decided to go this route.

In doing this, I’ve discovered that the older son has a deadly combination of issues: ADHD and perfectionism. I didn’t quite understand how the two fed into each other, but I can definitely see it now.

The older son also had the disadvantage of not working in the classes with peers. The first few he did were in print rather than online. He would struggle for days to complete a single assignment, and it didn’t make sense to me at first.

Another thing I found odd was how one of his teachers was initially very abrupt with him. It didn’t take long before she had completely changed her tune and was being incredibly nice and encouraging, which I thought was odd.

The second set of classes have been online and part of the assignments involved discussing things in a forum, so the student could see what the other students had submitted. This was an eye-opening experience for me. It also helped me make sense of his teacher’s dramatic change in behavior.

After watching him and seeing what other students have submitted, I realized three things:

1 – He can easily and quickly finish things that are simple.

2 – When things appear to be more difficult and/or time-consuming, he has difficulty concentrating and finds himself unable to stay on task.

3 – Part of the reason things are difficult and/or time-consuming is because he has seriously high expectations for himself that are way beyond what is often required.

I’m not saying he doesn’t have ADHD, because he most certainly does. We tried for years to forego medication. One day, he came to me and said he couldn’t even concentrate on projects he wanted to do for fun, so we opted at that point to look at something to help. (He does take meds, but it’s the lowest dose that’s effective.)

However, in homeschooling him, neither of us had a reference for what a ‘typical’ high schooler should be doing in his classes. He would give me an assignment, and we would spend a lot of time revising it. He worked very hard, but progress was slow. In one or two cases, he would hand things in half done because of lack of time.

What surprised me is that even the items he handed in half done or that were rough drafts often came back with exceptional grades. I remember one assignment full of rough drafts of short essays which he aced. I couldn’t figure it out.

The problem is that both of us really expect a lot out of him, and I learned, after seeing work that other students were doing, that it was likely too much. Far too much. While he was going into a detailed analysis of similarities because characters from two different novels set in two completely different cultural and temporal reference frames, it appears his fellow students who likely are trying their hardest, are writing something much more simplistic. They are being told to elaborate, and he’s being told to eschew obfuscation.

The thing that has me concerned is that college is around the corner, and I worry that he’s going to continue to hold himself to those standards, even when it is so obviously working against him. He struggles with the idea that it’s better to just hand something in, even if incomplete (by his standards), than to turn it in late, though perfect.

A lot of perfectionists deal with this. I have told him that it’s not a bad trait, but that he needs to save it for the things that are really important to him. If he wants to write the Great American Novel that people will pore over and debate and analyze, that is the time to be a perfectionist. If he’s handing in an assignment that fulfills the requirements laid out by the teacher, who likely will spend ten minutes skimming the entry, being a perfectionist is really not going to help. He needs to learn to walk that line. To some extent, we all do.

You could be a teacher October 16, 2013

Posted by mareserinitatis in career, education, feminism, research, science, teaching, work, younger son.Tags: education, high school, higher education, math, teaching, younger son

2 comments

As we were settling in for the ride home after swimming, the younger son asked, “Mom, you’re good at math, right?”

As we were settling in for the ride home after swimming, the younger son asked, “Mom, you’re good at math, right?”

The older boy snickered.

“I like to think so,” I responded.

There was a brief silence followed by, “Welllll………you’re good at math, and you’re a teacher…maybe you should teach math at a high school!”

What followed was a long explanation about how I just physically can’t handle the idea of teaching K-12. Teaching 6 hours a day, grading, prep, etc. Actually, it’s mostly the teaching. Teaching more than 4 hours turns me into a puddle that can’t function until I’ve had a good night’s sleep. Teaching high school is not the ideal profession for introverts. There’s also the fact that, frankly, it would get boring to teach high school math after more than a year or two. The math is what interests me more than the challenge of helping students to understand (though that is an interesting problem when the material is also sufficiently intellectually stimulating). I think he gets it, but he still likes the idea of his mom as a math teacher.

This did bring to the surface some thoughts I’ve been mulling over. Does he see me as a teacher because he already knows I teach or does gender roles have something to do with it? I’ve been pondering this a lot because I get the sense that there are some academics who really do view teaching through a gendered lens and therefore think I’d be better off at a community or liberal arts college. In fact, I imagine there’s a blog post where I discussed someone telling me as much, but I’m not going to dig it out now.

One thing that has occurred to me is that, if I want people to look at my research, I may actually actively have to avoid things that will stick ‘teacher’ into their heads when they think of me. That is, it’s probably a good idea to actively avoid involvement in education conferences and societies except at a cursory level. Teaching should be kept at a minimum. I enjoy the service work component and the idea of exploring interesting aspects of STEM education. I also really enjoy interacting with students (but not all day long). I don’t like the idea that it means that my other abilities and accomplishments will be overlooked. Maybe that’s taking things too far, but I don’t really know how to cement the ‘researcher’ thing into people’s brains unless that’s the only thing they see when looking at my CV. Maybe once the ‘teacher’ version of me has been wiped clean, it’ll be okay to begin dabbling in serious educational research pursuits.

That’s obviously not what my son was worried about. He simply wants me to have a job I enjoy…and maybe there’s a bit of an ulterior motive as he hopes I’d be home more during the summers. It’s a nice idea, but the other nine months of the year probably wouldn’t be all that enjoyable for me…especially if doing research was secondary, or worse, nonexistent.

All that being said, I think that if I do ever become a math teacher, I want the above tshirt. (You can get it here, if you’re curious.)

This is NOT what a scientist looks like August 26, 2013

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, science, younger son.Tags: education, science, Scientists, stereotypes

1 comment so far

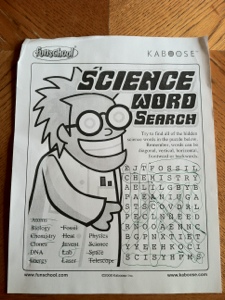

The younger son’s school is starting a new science curriculum this year. Mike and I were very excited to learn about it as it’s supposed to emphasize hands-on learning. But this came home today, and I could only roll my eyes. Can you see what’s wrong?

A tale of two colleges April 2, 2013

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, gifted, older son, societal commentary, teaching.Tags: college, education, gifted education, higher education, older son

2 comments

I quickly came to the realization, after coming up with a list of potential colleges for the older boy, that we should try to visit some campuses now. I teach in the fall and taking time off during the week would only be possible around Thanksgiving, so this would be our last chance before applications are due. We hurriedly put together an itinerary and are doing part 1 of the college tour. (Part 2 will be in another, more distant state and will therefore have to occur during the summer sometime.)

The first college we visited was close to the top of the list. It’s a nice state school in a great town, and the older boy was very psyched about the visit. Everything sounded great on the tour, and the overview presentation only reaffirmed that it would be great. Then, however, we talked to an admissions counselor. We explained that older son has his GED, has done or will soon finish all the necessary testing, and that most of his curriculum was courses that he CLEPed.

The counselor informed us that we needed to do the whole transcript thing and affirm that he had taken four years of English, math, etc. I took a deep breath and then asked, “But, does he really have to have four years of English classes, for example, when he’s already demonstrated he can do college-level work in the area?”

“Yes, the tests show he has some knowledge, but we need to see that he’s done the work.”

My first reaction was to wonder who in the world could really pass these tests without doing the work, in some form or another. Second, I wondered why bother saying you accept a GED if this is what is required. Third, I got angry. Is education really about parking your butt in a seat for four years and not so much about learning anything? Is that what will be expected of him at this college?

The worst reaction was when I looked at the older son and saw his face fall. “Oh no,” I thought. “I’ve totally screwed this kid over. How will he get into college? Did I just mess up his life because of insistence that he become prisoner to my educational values while ignoring pragmatism?” Of course, that’s utterly ridiculous. When you’re dealing with a kid who is gifted and learning disabled, the best way to ruin his or her life is to leave them in a situation where they are obviously miserable and non-functioning, which then destroys their self-confidence and motivation. No, I got him into a situation where he was learning and was able to demonstrate that using objective criteria.

Still, after that meeting, the older boy and I were both awfully bummed. After hearing a similar but slightly less uptight message at another school, I started wondering if maybe we needed to worry less about other criteria and find some places that were more friendly to homeschoolers. I’ve realized that we really need to talk to admissions counselors at each of these schools and see if there’s even any point in him applying if they’re going to be extremely skeptical of his accomplishments.

Today, we may have hit the jackpot, however. After getting an overview of this school’s very flexible and creative approach to education, we talked with someone about the older boy’s background and what we’d been doing for schooling. Rather than the reaction we had been getting, they said it sounded like he was rather accomplished. They were fine with his GED, saying that gave them a very good normative comparison, and were impressed with his accomplishments thus far with his CLEPs. That college is, as of right now, at the top of older son’s list. He’s really happy to have found a place that doesn’t view getting a degree as simply a matter of checking off items on a list of requirements.

All of this made me curious. I never knew why he had issues in high school, but it was obvious that once he took his GED and started studying for his CLEPs that he was suddenly excited about learning. I decided to ask him. His response was that he hated how you had to do everything together in high school. The stuff that was easy, they would drag out forever. When they got to stuff that he wanted to look at more carefully or had trouble understanding, he said they’d rush through it.

“College is a lot different, though,” he said. “You’re expected to do a lot of work on your own, so I’ll be able to spend a lot more time when I feel like I need to and, if the class is going slow, I can spend my study time working ahead.”

Apparently something sunk in as he knows he can take responsibility for his own learning. That, in my mind, is very much the point. Education shouldn’t be just a process that happens to you.

The socialization question, homeschooled and gifted children March 9, 2013

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, gifted, homeschooling, papers, research, teaching.Tags: education, gifted, gifted education, homeschooling, research

4 comments

A very long time ago, I was asked to teach a workshop for the Homeschool Association of California annual conference. It had to do with computers, though I don’t remember what. What I do remember, however, was expecting that I’d be dealing with a bunch of antisocial technophobes.

I couldn’t have been more off the mark than I was. I only had a handful of kids, but they were definitely not technophobes. Admittedly this is probably a self-selecting group because, after all, no one was forcing them to go to the workshop. But what surprised me even more was that they were very sociable. Unlike other high school kids I’d worked with, they didn’t seem intimidated by me or afraid to ask questions. I remember coming out of that workshop and feeling like I’d been slapped upside the head.

The thing I realized from that is my assumption that children schooled at home were anti-social was due strictly to my lack of imagination. I had assumed that if you didn’t spend all day in a room with other kids that you wouldn’t learn to interact at all. It’s not that I’d ever met many homeschoolers. In fact, it was probably my lack of exposure to the culture that made me construct my own version of how they must behave.

Interestingly enough, I find that it’s the one thing that most non-homeschoolers key on: in order to be ‘properly’ socialized, you have to go to school. After spending time around homeschoolers, and recounting my own school experience, I have always been extremely skeptical of that argument. It didn’t help when my older son spent a year going to middle school full time only to come out of it incredibly angry because of the horrid bullying, by students and teachers alike, that he’d encountered.

It’s interesting to me that this question also brought up in response to doing anything different for gifted children in normal schools. That is, there is the argument that grouping children by ability or accelerating their academic curriculum means that kids won’t learn to appreciate diversity and get along with other people. Most people assume that putting gifted kids in different groups or classrooms is bad for everyone.

I hate assumptions, though. I have, over time, come across studies here and there saying that, in general, these assumptions were wrong. I can only think of one study that said ability grouping had negative consequences, and one study on homeschooling that showed a neutral outcome on homeschooling. The topic came up in a discussion with someone, and I thought it was high time for me to make sure I wasn’t blowing smoke.

Unfortunately, the research on both groups is relatively sparse. I suppose it’s not a compelling interest for the majority of the population, so not a lot of resources are put toward it. I am kind of a fan of summary papers, mostly because they save a lot of time by summarizing the results from several different studies while noting the drawbacks of each. In that vein, I managed to come across one for each group, although both are rather ‘old’ by my standards. The paper on gifted socialization was from 1993, while the one on homeschooling was from 2000. (Social science progresses far too slowly for my tastes.)

For the gifted group, Karen Rogers wrote a synopsis of a paper which talks about several different forms of grouping and acceleration. The paper looks at 13 different studies on gifted accelerations methods. She found that academically, almost all methods had positive effects. If you look the psychological and social effects, the were probably neutral. Some forms of acceleration resulted in positive outcomes, some in negative. Her conclusion was:

What seems evident about the spotty research on socialization and psychological effects when grouping by ability is that no pattern of improvement or decline can be established. It is likely that there are many personal, environmental, family, and other extraneous variables that affect self-esteem and socialization more directly than the practice of grouping itself.

The studies that discussed homeschooling were covered in a paper by Medlin. Surprisingly, there were a lot more studies covered in this paper than on gifted education. Medlin broke down the studies into three groups, each addressing a different question. First, do homeschool children participate in the daily activities in the communities? The results indicated that they encountered just as many people as public schooled children, often of a more diverse background, and were more active in extra-curriculars than their public school counterparts. The second question was whether homeschooled children acquired the rules of behavior and systems of beliefs and attitudes they needed. (I keep feeling like there’s a comma missing in that…) While detractors may be pretty upset at this, the conclusion was that, in most cases, homeschool children actually fared better in these studies. Admittedly, though, the studies were hardly taking large numbers of students into consideration. There was speculation on this set of results:

Smedley speculated that the family “more accurately mirrors the outside society” than does the traditional school environment, with its “unnatural” age segregation.

This particular view stands out because it’s a view I see reflected a lot in analysis of gifted education, too: age grouping is unnatural and ability grouping is more likely to occur in real life.

Finally, Medlin asks whether homeschooled students end up doing okay as adults. There are very few studies in this section, but the conclusion from those studies was that they not only do fine, but tend to take on a lot of leadership roles. (I do know there was a study commissioned by the HSLDA a few years ago that came to similar conclusions, but I find a bit of conflict of interest in that one given who paid for it.)

If there’s anything people should be taking out of these studies, it’s that our adherence to age-based grouping of random kids really doesn’t provide the beneficial socialization we think it does and may, in fact, have some pretty negative impacts. In fact, I recently came across and article called, “Why you truly never leave high school,” that talks about those negative effects and how they may actually be carried with us into our adult lives. (Yes, I do realize some of the conclusions make the title a stretch, but it’s food for thought.) Given the presence of issues like bullying that have gotten more air play over the past few years, I’m very surprised people haven’t realized that it could, in fact, be detrimental.

One giant leap…sideways October 2, 2012

Posted by mareserinitatis in engineering, teaching.Tags: education, teaching

add a comment

One of the assignments I give my students is to do a group presentation. For this assignment, each group discusses one of eight subfields of electrical engineering in front of the class. It seemed like a good idea because having me present for an hour on different fields seemed kind of absurd.

Last year’s effort was a disaster. I do realize these kids are college freshmen, but I was surprised at what a mess the presentations were. I decided it was probably my fault: they weren’t prepared and needed more guidance.

This year, I gave each group a sheet where I laid out what I wanted them to cover, how to break it up, and a couple starting points for doing their research. I figured it was bound to go better than last year. I was partially right. Some of the groups did an excellent job on their presentation. The groups that didn’t at least included some of what I wanted.

However, I’d say that the class really didn’t get much more out of this year’s presentation than last year. This leaves me wondering if I should scrap this approach to the project. However, I’d really like the students to have a better idea of what sort of areas they’re interested in when we start looking at schedules and they begin picking electives. I’m contemplating just giving them a list of web pages covered each subfield and having them write up a summary of their favorite two.

There are some rather practical implications in dealing with the problem this way. First, it means more grading for me. Second, it effectively eliminates two class periods worth of activities for me, and I’m not sure that I want to add anything in to replace them. I’m not a fan of filling up space just because, but when your class meets once a week 16 weeks, two weeks can have an impact. Finally, how can I be sure they are exposed to all of them and not just the first one that looks cool?

I hope that, if nothing else, the students are getting the idea of how frustrating it can be to watch someone else give a bad presentation.

Some thoughts (like, a million or so) on instructional technologies July 10, 2012

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, family, gifted, grad school, homeschooling, math, older son, research, science, societal commentary, teaching, younger son.Tags: brain rules, education, family, higher education, learning, learning disabilities, older son, online learning, schedules, science education, teaching, technology, UDL, universal design for learning, universities, younger son

3 comments

I’ve been having a discussion with Massimo about his post on instructional technology. Despite what I’ve already said, I have a lot more thoughts, so it’s just easier to write it out as a blog post (or maybe more than one).

I think I’m going to start by defining some things about how classrooms operate online. First, you have what I would call the Udacity (or maybe Khan Academy) model. This is a model where you basically watch a lecture online, complete and submit homework assignments online, and discuss things via discussion boards (or Blackboard or Moodle). The second model is completely computerized – all the lessons are presented via a reading or lecture, and the bulk of the course is completing problems. Both my sons have used the former method to learn math. One uses EPGY and the other uses Aleks. On top of these choices for online education, there are in-class courses, mixed (some components online and others in a classroom or lab), and earning credit by exam, such as AP, CLEP, or DANTE exams.

If you look at these options from the point of view of a university, some of these options for educating students are going to be more appealing than others. Credit by exam, of course, is going to be the least appealing. The university gets a fee for administering the exam but pretty much nothing else. Many universities simply will not accept them, but there are a lot of them (mostly non-elite schools) that will.

The other one that is bad from a university POV is the completely computerized model. It works incredibly well for things like math and some sciences because it basically moves working from a textbook to working on the computer. Also, most of the programs are adaptive in that, if you’re having difficulty with a concept, it will first give you additional problems. If this doesn’t seem to be helping, it will pull you off that topic and put you on to another, waiting a while before it allows you to revisit the difficult topic. (I believe K12 uses a completely computerized model for all courses, but I have no experience with it and can’t say how well it works for language or social science-type courses.) In a classroom where one person is a facilitator supervising several students working on the course, this is a very cost effective method, and a lot of elementary and secondary schools are beginning to utilize it. When doing it for online education, however, it represents an expense that is more, generally speaking, than hiring an individual to teach a class. The majority of tuition money would be spent on licensing (as there are already several good ones out there) or development of a program (which may not compete well with pre-existing products) and not going into university coffers. Also, why offer something that everyone else can offer, too? That’s certainly not going to set you apart in terms of attracting students. Therefore, universities are more likely to want to have in-class courses, mixed, or online courses that utilize the Udacity model.

In the discussion Massimo’s final comment was this:

I was not aware that there is now solid research showing that online education is superior to classroom teaching for the vast majority of students (I assume that at Stanford they no longer offer classroom-based math courses — it would make no sense to have continued, given that online courses work better). I am surprised that classroom-based education still exists at all, and that so many of us still believe that it is better — but I am sure society will soon abandon this useless relic of a time past, and embrace the more effective online education.

Here’s the problem: there are decades of research showing that online education is, at the very least, equally effective for most students and significantly better for other students. So why aren’t we using it more? I could also state that lectures have been been shown to be one of the poorest forms of teaching known to man, so why do we continue to use it so much? Turns out, there’s an answer. In this journal called Science (you may have heard of it), they ask exactly this question about interactive teaching and inquiry-based classrooms:

Given the widespread agreement, it may seem surprising that change has not progressed rapidly nor been driven by the research universities as a collective force. Instead, reform has been initiated by a few pioneers, while many other scientists have actively resisted changing their teaching. So why do outstanding scientists who demand rigorous proof for scientific assertions in their research continue to use and, indeed defend on the basis of intuition alone, teaching methods that are not the most effective? Many scientists are still unaware of the data and analyses that demonstrate the effiectiveness of active learning techniques. Others may distrust the data because they see scientists who have flourished in the current educational system. Still others feel intimidated by the challenge of learning new teaching methods or may fear that identification as teachers will reduce their credibility as researchers.

I’d like to note that this was published in 2004, almost a decade ago. Here we are, 8 years later, and from my observation, active teaching strategies are seldom used in most classrooms.

I think it’s safe to say that this is the same set of problems faced with online education. I would also add that people who learn well in the classroom have a hard time understanding that others may learn as well or better using a different medium. Or there’s just simply the problem that they’re afraid they’re going to lose their jobs. (I only see this as likely in the scenario colleges would somehow try to implement completely computerized online classes…but you can see my comments on that above.)

One major issue that I see is how few college instructors really understand how people learn. They learned well through a lecture style course, and so they assume that it is obviously the best way to learn. I personally think that every instructor ought to have at least one course in educational neuroscience so that they understand how lousy lectures really are as well as so that they may communicate to their students how they ought to try to approach learning and studying. (This was a significant part of the class I taught to incoming engineering students last year, but not all places have a course where you can cover topics like that.) I do realize that such a course is not available at most universities, but I don’t think that should prevent one from accessing this knowledge. I would suggest that one who has never taken such a course invest some time in the course materials available online (are you feeling the irony?) at Harvard. Those opposed to online education can read the book Brain Rules, which was used as the text for the course. (Of course, if you are opposed to online education, I hope you’re reading an actual paperback rather than downloading it onto your iPad.)

Massimo also says:

I am not disputing that online education may be the only/best option for some — but, from it being a valid option for some, to it replacing classroom teaching foreveryone, there is a bit of a leap, don’t you think ?

No, I don’t think so. There are two reasons why I think this. First, teachers who embrace online learning are more likely to embrace other technology that is likely to enhance learning. Generally, this will enhance learning beyond anything that is likely to occur in a lecture-based class that occurs in a classroom. Despite what some people may say, research shows (read Brain Rules) that learning which is multisensory (like watching YouTube clips) is better for you than sitting in a lecture. Images will convey more information than talking, and video (or seeing something in action) conveys more information than straight images. Sitting in a lab is likely the best environment of all. Online learning also is likely to be able to keep people’s attention. (If you read Brain Rules, you’ll come to find that most people can only focus for about ten minutes, and then they need something to restimulate their attention.)

Second, I think accessibility is a huge issue in education. I have one parent who found it incredibly difficult to finish a degree (and she never did) because she had a choice between quitting her job to take classes at the local university, which were only offered during the day, and taking night classes at an expensive private college. I have a sibling who is currently finishing a degree in accounting online because she lives two hours from a university and works 4-10s. How is she supposed to finish a degree at a school in those circumstances? There are a lot of people in similar situations who would otherwise be unable to earn a degree. In fact, my husband earned his MS through Penn State through a Navy program where he took some classes at the university and some through a video link…well over a decade ago. He said he would’ve been unlikely to pursue a degree if he’d had to drive across Puget Sound (he was in the Seattle area at the time) evenings for two or three years.

Okay, so obviously I know a lot of people who have benefitted from these sorts of things. So why do I think it could work for everyone? I think this is a basic principle behind Universal Design for Learning: the notion is that if you design a curriculum that helps people with difficulties and disabilities, you’re going to help many other people as well. Our brains work on a continuum, and while not everyone may have learning disabilities, they may operate in a region where learning may be difficult, if not disabling, when it’s presented a certain way. Therefore, if you design materials to teach someone who is hearing impaired, for instance, you’ll likely help a lot of people who may have difficulty with ingesting information through auditory means in general. (Lest you think this must be a small part of the population, take into consideration that I was working toward a master’s degree before I found out that I likely have some sort of auditory processing disorder…and only because my son was diagnosed with one. Smart people can often do well even with learning disabilities because they often have other ways to compensate…but it can be frustrating for them, nonetheless. I wrote a post on this topic a while ago.)

So what does this have to do with online learning? I can give a concrete example: my older son is ADHD and had auditory processing disorder. He really struggles sitting in a normal classroom and, for most of his life, his teachers told me he couldn’t possibly be gifted because of his classroom performance despite the fact that I had documented evidence to the contrary. We took him out of the classroom, and he started earning college-level credits through CLEP exams beginning his freshman year of high school…working independently, primarily through reading. As I mentioned above, he does all of his math through Aleks. He does extremely well on pretty much any type of standardizes examination. I can easily see a kid like him, even with less problems, having huge difficulties sitting in a college classroom but being able to handle an online class very easily in no small part because the method of presentation. So why can’t this help someone who is less distractable?

Take it a step further. If online learning is ideal for people who have jobs and families and can work in the evenings but not get to classes, why can’t it also work for students living in dorms or even at home? Maybe some of them find that they concentrate best at night and it is preferable to sitting in a large, crowded, warm, boring classroom at 8 a.m. (And yes, people do function on different clocks.) Aren’t you benefitting the student by allowing them to work at their peak time?

I’m not saying everyone will take advantage of this, but I think it ought to be an option for many people. Some people really thrive on personal interaction and keeping them out of a classroom would inhibit them from learning. Some people don’t. The ideal situation is where students have choices and options.

I think the final thing I have to say on this topic is that the real problem, in my mind, is that teachers see themselves as essential to the learning process. Really, the one thing I’ve learned going through graduate school and homeschooling my kids is that teachers are more often an impediment. The university functions to teach students, and yet, in many cases, students are quite capable of learning the materials on their own. That’s really the reason behind homework: you learn it far better by doing it than by sitting and listening to someone talk about it. In reality, students are still learning on their own. The role of the university is to focus the effort, speed up the process, and assess performance. Students are not necessarily learning anything from their classes that they cannot learn on their own…and in fact, they may be learning it less deeply than if they did it on their own.

I find this ironic given that the other aspect of a university is research: people are expected to learn new things and create new knowledge all the time. If learning really only happens meaningfully in a classroom, then research couldn’t exist. I can’t wrap my head around the fact that researchers who learn things on their own all the time will turn around and claim that undergraduates somehow lack that ability.

My conclusion, therefore, is that online education should seriously be considered as an alternative whenever available. I think it democratizes education and makes a better environment for learning for a significant portion of students. The reason we haven’t shifted to these models is mostly because professors, on the whole, are unwilling to consider that it should be done another way and are uninformed about the benefits.

Why parenting sucks… May 25, 2012

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, gifted, math, teaching, younger son.Tags: education, gifted education, math, standardized exams, testing, younger son

11 comments

Now that the school year is over, I can finally discuss one thing that’s been driving me nuts for the past couple weeks.

Most of you know that I’ve been volunteering to work with a group in my son’s class that’s slightly ahead in math. The teacher was doing some grouping to help the kids who were struggling and more or less leaving the other ones to do “enrichment activities” for an additional twenty minutes outside of normal math time every day. I was going in once a week to help with the advanced group, although that evolved into reading math stories to the whole class every other week.

One day was very odd. As I sat down to work with the ‘advanced’ group, the younger son started talking. He started explaining addition and multiplicative identities to the other kids, but it was obvious they didn’t know what he was talking about. At first, I tried to get back to what I’d planned on discussing, but I also didn’t want to make him feel like he was being shushed. So when the other kids started this eye-roll, “here he goes again” type of body language, I tried to augment what he was saying. I wondered how often this type of thing was happening. I felt bad about the whole thing because the kids seemed interested when I was talking about it. However, here’s the younger son, feeling like he can talk to these other kids about some of the math he was doing at home, and they don’t understand and are blowing him off.

Unfortunately, I know how he feels because this happens to me as an adult, almost always when I’m talking to my kids’ teachers. I have always gotten the feeling that they think I don’t understand children or how they work. I obviously am just one of those parents that’s overestimating my child’s intelligence and pushing him beyond his ability. If my children really were ‘gifted’ (always said with a sneer, if the dreaded word is even spoken at all), then they wouldn’t behave the way they do. (I think this means they expect my kids to sit still and be compliant.) And I’m most definitely not competent enough to handle educating my own child.

In fact, it happened again very recently. The younger son’s end of year test scores came back, and all of the focus was on one subtest where he’s “right in with his peers”. That is, a full year ahead of national norms. They’re very concerned about his progress because of that subtest and wanted him to spend next year in the normal classroom to ‘get him back on track’. (Because working a year behind his current achievement level helps him how????) Very conveniently, they ignore the subtest where he’s four years ahead…and the other two or three where he’s still very far ahead of his classmates, as well. They use that one subtest as evidence that I’m doing a lousy job teaching him math at home.

The good news is that they’re going to let him continue to use his current math curriculum, only he will be doing it at school in the fall. I have a few reservations (mostly that he won’t get the help he needs), but I have hopes that just maybe they’ll start believing me. I know it’s hard to believe a kid can go from getting teary-eyed about getting subtraction problems wrong to gleefully manipulating fractions and decimals in a single year. On the other hand, I am pretty sure he’s said things that would make them realize he knows some of this stuff…but I suspect they just blew it off or attributed it to his “overactive imagination”.

Fed up with standardized tests May 19, 2012

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, gifted, teaching, Uncategorized.Tags: education, gifted, gifted education, standardized exams, teaching

10 comments

When I was a kid, I remember taking Iowa Basics tests every couple years. I remember this because I was both stunned and disappointed. I was usually impressed because my grade equivalencies placed me at least three grades ahead of then current placement with the gap widening as time went on. The disappointment was because nothing ever came of it. I sort of assumed that everyone I was going to school with must have similar scores because I was kept with the same people, in the same grade, without even so much an acknowledgement.

Well, okay, there was an acknowledgement – there were usually comments about how my math computation scores were so much lower than everything else. (This is what led me to believe, for many years, that I was bad at math.)

My kids haven’t used Iowa Basics, and I find this very disappointing. In a move that I can only assume is a result of No Child Left Behind (or, as I affectionately like to refer to it, the “Lake Wobegon Law” because everyone must be above average), there has been a shift away from tests like Stanford Achievement or Iowa Basics to NWEA Map testing.

The only way I can describe this is useless info that’s providing a moving target. The test provides percentiles and approximate ranges for competencies in various subfields. It is frequently renormed. In many respects, it’s the same as any other standardized test.

My beef is that, as far as I can tell, the only purpose of the test is to see how your student(s) compare with the rest of your district or nationally. On the other hand, I will say that it’s not the only one that does this. However, it seems like there are a lot of schools moving this way, and I see it as a huge detriment. The reason is that I don’t think you can make decisions about a child based strictly on their performance compared to a norm. However, that’s exactly what teachers want to do. They see an area of relative weakness in a child and want to hold them to that level for all of their abilities. I am left to ponder why it is they never want the child to be working at the level where they are capable and make an attempt to bring the weak areas up to par with the strong areas. Of course, if you have nothing to determine where they’re actually achieving, it’s hard to implement that type of education.

This leads me to wonder: how does a child working at age level help them to develop skills above age level? If you’re teaching a child stuff s/he already knows, aren’t you just holding them back?

The complaints I received about my ‘lousy’ math computation scores are one example of this. I have several tests showing this problem which constantly elicited comments from teachers about how I was poor at math. I get the impression that they looked for personal weaknesses but never really made the connection that my average was different than most of the other kids. Their solution, therefore, was to have me work on more computation at grade level.

Scores that only consist of a percentage relative to norms tell you is that one’s performance relative to everyone else may be an area of weakness. It doesn’t tell you, however, where you’re really achieving. It’s a bit different if you have a grade equivalency sitting next to the norms. It turns out that my ‘lousy’ math computation scores implied that my computation was equivalent to the average child two grades ahead of me. And it should be fairly obvious that if they wanted to me to be achieving more strongly in computation, they would have been giving me more computation at 2-3 years ahead of grade level. Unfortunately, that’s not what happened, and most often, it’s still not. It’s a lot harder to dismiss a child’s achievements when you have a solid basis of comparison (a kid two or three years older) than some vague percentile. Those percentiles don’t give teachers a true picture of achievement; how many teachers have frequency tables for a normal distribution sitting nearby? My impression is that it leaves them only feeling that when a child is at a very high level, the child is learning and thriving in their current environment. They have the mistaken impression that the child is having their needs met, when in reality, the child could be seriously underperforming relative to their potential. Likewise, they may get the impression that a child is struggling but fail to realize that it’s because they lack basics from prior years.

I therefore would like tests to go back to giving grade equivalencies. I think this illuminates the level of child achievement and gives teachers a better idea of what they are actually dealing with. There is a good amount of research showing that teachers are actually some of the worst identifiers of children’s intellectual gifts, and taking away the frame of reference that grade equivalencies provide is going to make it worse for the child and parents or other advocates.

I also blog at Engineer Blogs, home away from home to some of the best engineering blogs.

I also blog at Engineer Blogs, home away from home to some of the best engineering blogs.

If you send your kid to public school, you’re a dunce September 1, 2013

Posted by mareserinitatis in education, homeschooling, societal commentary.Tags: education, homeschooling, public schools, school, stupid

3 comments

That’s a strong statement, calling someone a dunce because they allow their children to go to a school that’s provided for free and, in most cases, even required by law. Why would anyone say that? I’m not sure, but it was about as useful as the title of an article on Slate: “If you send your kid to private school, you are a bad person.” Generalizations are, in general, pointless things, and they aren’t much better as titles.

The article itself, however, was downright appalling. The author, Allison Benedikt, starts out by saying:

That’s probably the only point in the whole article I can agree with. The whole thing was a judgemental screed against people who don’t send their kids to public schools. None of it was backed up with evidence or even anything remotely resembling solid reasoning. She discusses the fact that she attended public schools, and after reading her complete inability to form a cohesive argument, I dare say she made me even more convinced that our public schools have gone down the tubes.

She did have some reasons for her premise that those of us who send our kids to private schools are bad people. She starts by saying that if everyone would send their kids to public school, they would improve…it would just take ‘a generation or two’. You see, those of us who have the means to send our kids to private school are just supposed to sacrifice our kids’ and grandkids’ educational needs to meet some utopian goal that has a small likelihood of occurring. It apparently never occurred to her that she has made exactly the wrong argument to these people: people who send their kids to private schools may have several reasons for doing so, but I would guess that the main three are going to be that they strongly value education, they strongly value the ethical systems taught at some of these schools, and they are worried about what I would generally call ‘status issues’ (things like who their kids hang out with and perception of their families). Does she really think that parents who are that concerned about one or more of these three things is really willing to ‘sacrifice’ their kids? That’s the whole reason they’ve elected to go with private schools to begin with: the sacrifice of large sums of money is less important than the sacrifice of their kids’ education (and the things that go along with it). However, Benedikt wipes these issues away and says they’re not compelling. She started her whole argument by finding the most compelling way to isolate her audience.

In fact, she starts belittling education and claiming that you really don’t need those things. She is a perfect example, apparently, because her parents sent her to school and really didn’t care about those things. That is quite obvious given her line of reasoning…and, as I said above, compels me to want to send my kid to private school even more.

Benedikt says school is really about is interaction with other people. I won’t disagree that a large part of school is socialization, but I, of course, don’t buy this argument as I’ve written before about how public school is actually generally worse than options like homeschool when it comes to socialization. Throwing together a lot of immature people to learn socialization from each other results in, surprise surprise, lots of immature people. More adult interaction with those adults role-modeling mature behavior is a far better socialization system than the one present in most public schools. Again, this is actually an argument against the public schools, in my opinion.

Finally, Benedikt says that if only we redirected our private school endeavors to public schools, that would make everything better. Here, I can only assume she is incredibly naive on so many levels.

I will start by saying that I don’t hate the public schools. The notion of free education available for everyone is most definitely a public good and vital to maintaining democracy. However, I think that our public schools have some major problems. As the political right wing says, they don’t work to educate children. The structure is set up for teachers, not for students. As the left wing says, they are underfunded and undervalued. I think both sides have very valid arguments. Schools have, for generations, taught children using the least effective methods, mostly by people who aren’t well-educated themselves (particularly in the grade school years). They have a better handle on crowd control than educational psychology. On the other hand, they have to because of they way the public school system ties the hands of teachers.

There are so many educational reforms that would make the schools *work* but people are not interested in trying them out or are scared that it may affect their job security. Or they are just apathetic about education. I’m not talking about things like vouchers or charter schools. I mean things like making grade levels fluid, getting rid of grades, making the classroom a place where students are leading their learning and teachers are facilitators. The notion of allowing children to excel in areas of interest and take more time in areas of difficulty is almost heresy. In other words, what schools ought to be are places where kids really learn, where interaction provides useful feedback about knowledge and behavior, and where you’re not locked into doing something simply because of how old you are. Education needs to be tailored to the individual student because teaching to the average is useless for everyone.

These are the kinds of reforms that would bring parents back from the private schools. Simply saying that the schools would be better if all parents sent their kids to public school is naive, at best. It is as blind a solution to the problem as just shoving more money to the schools, privatizing schools, or forcing kids to pray in school. Almost every reform out there is completely blind to the fact that we are using teaching methods that actually fail to education children. If you don’t change our fundamental assumptions about how to educate students, you’re not going to get any different results.

I will say that I agree that it’s sad not more people take an interest in seeing public education thrive. However, part of the reason is that the way public education is conducted is virtually set in stone. It takes a divine act for most places to change even the smallest things. Too often, school teachers don’t have the time or knowledge to deal with individual students’ issues and the parent of such children is viewed as an enemy combatant. My choice as a parent then becomes whether I want to devote my time to change the outcome for my individual child through whatever means I have (for instance, by homeschooling or sending to private school) or continuously shoving an immovable object. If I had left either of my kids in public school, I wouldn’t have fought harder…I would have quit because of the futility in trying to work with most teachers and administrators who have no interest in seeing the system change.